HHG Studio

The most complete application to run High Harmonic Generation simulations

Main features

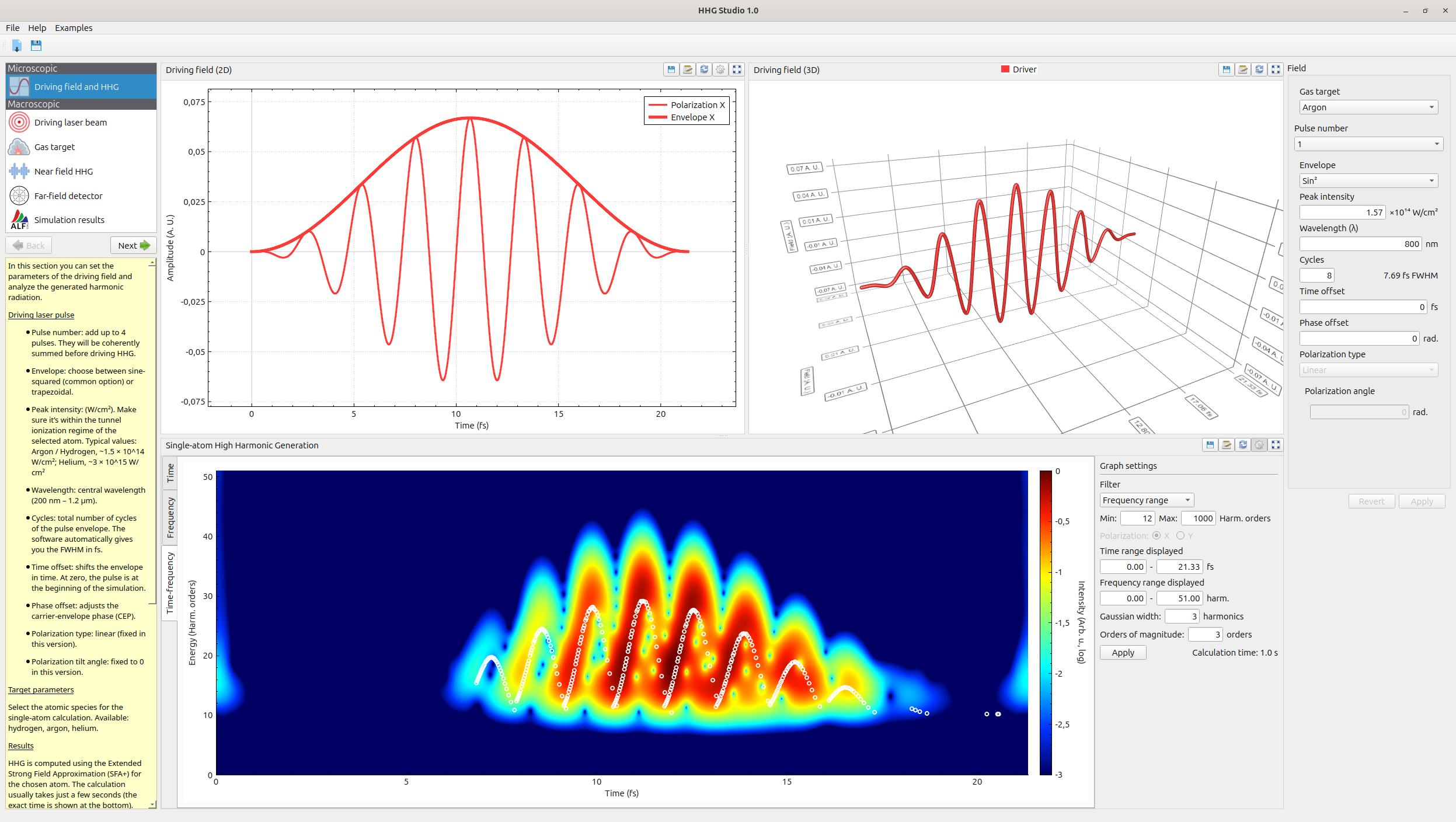

Define your custom driving field.

You can shape your driving field combining up to four laser pulses, configuring their wavelength, number of cycles, envelope, duration, CEP, polarization and more.

- Up to 4 driving laser pulses

- Visualize your configuration

- Preview microscopic HHG

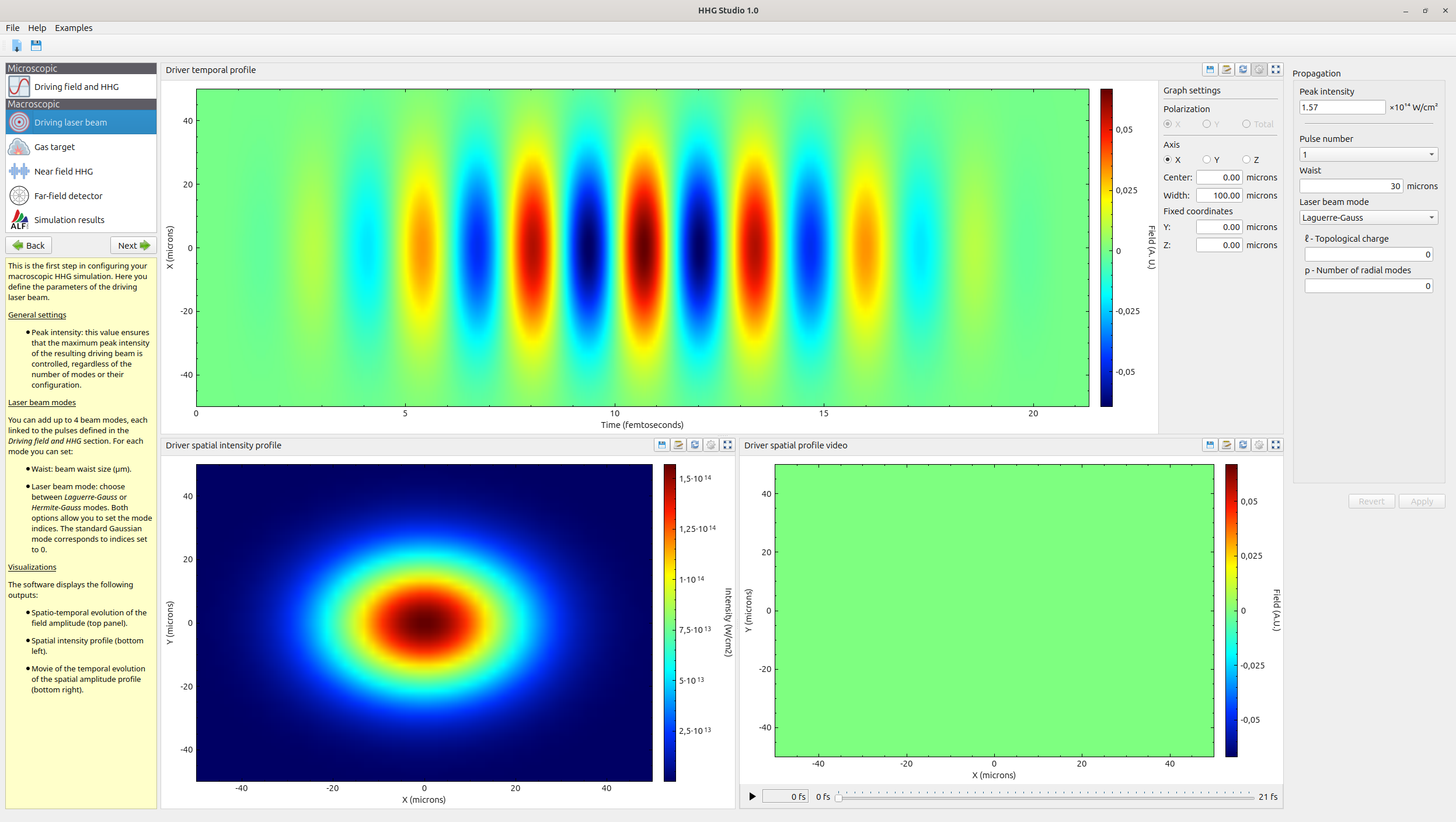

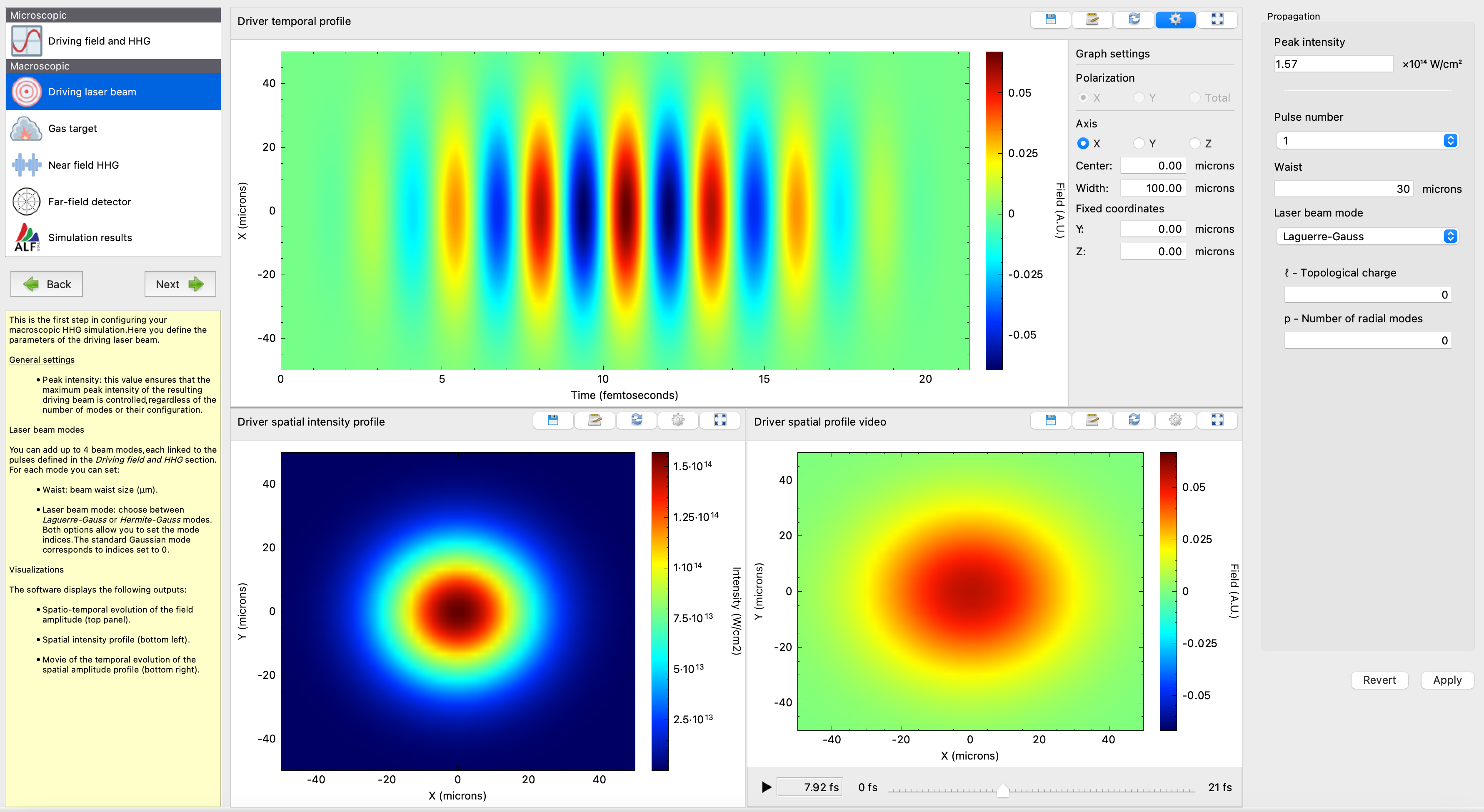

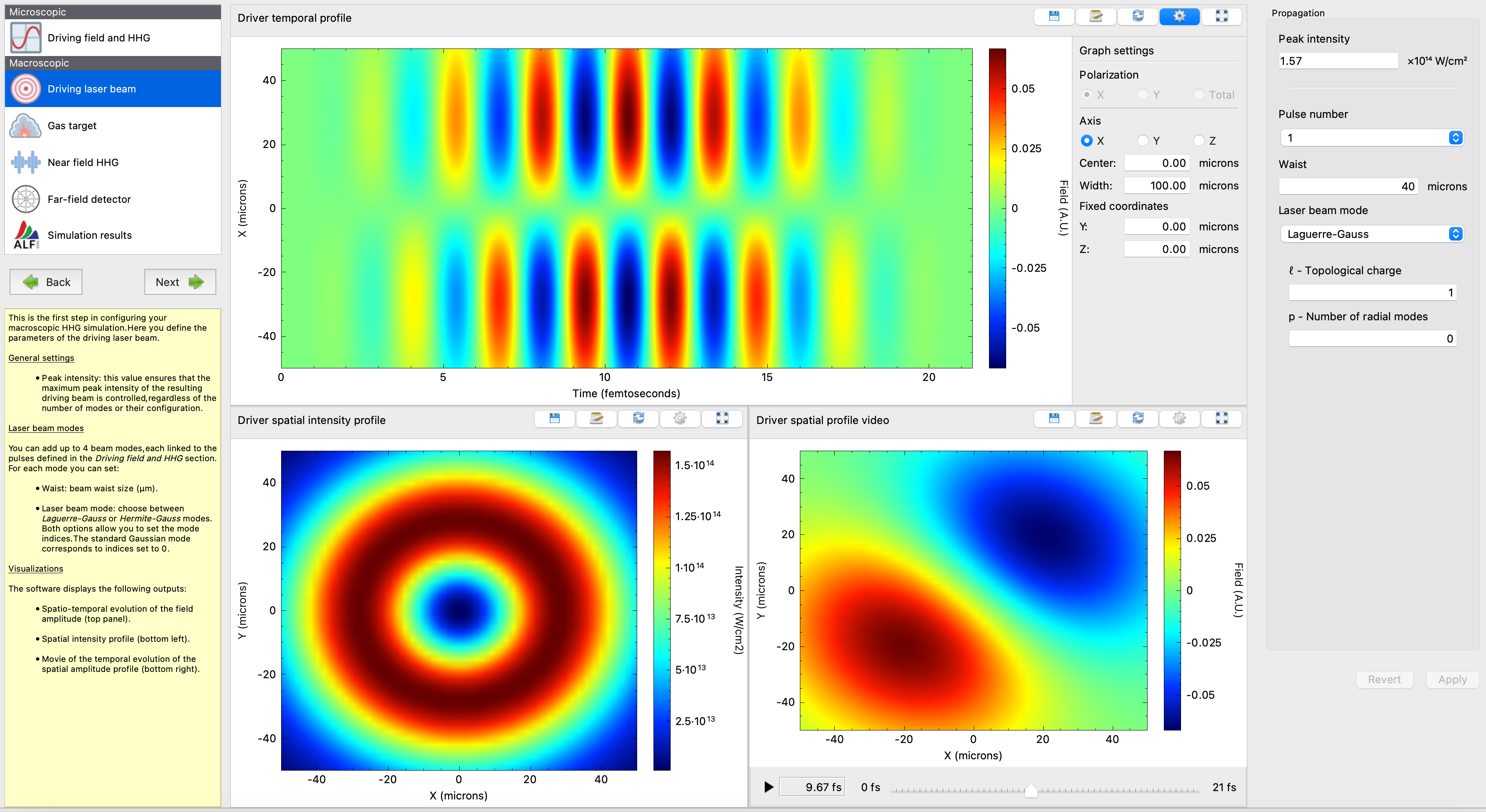

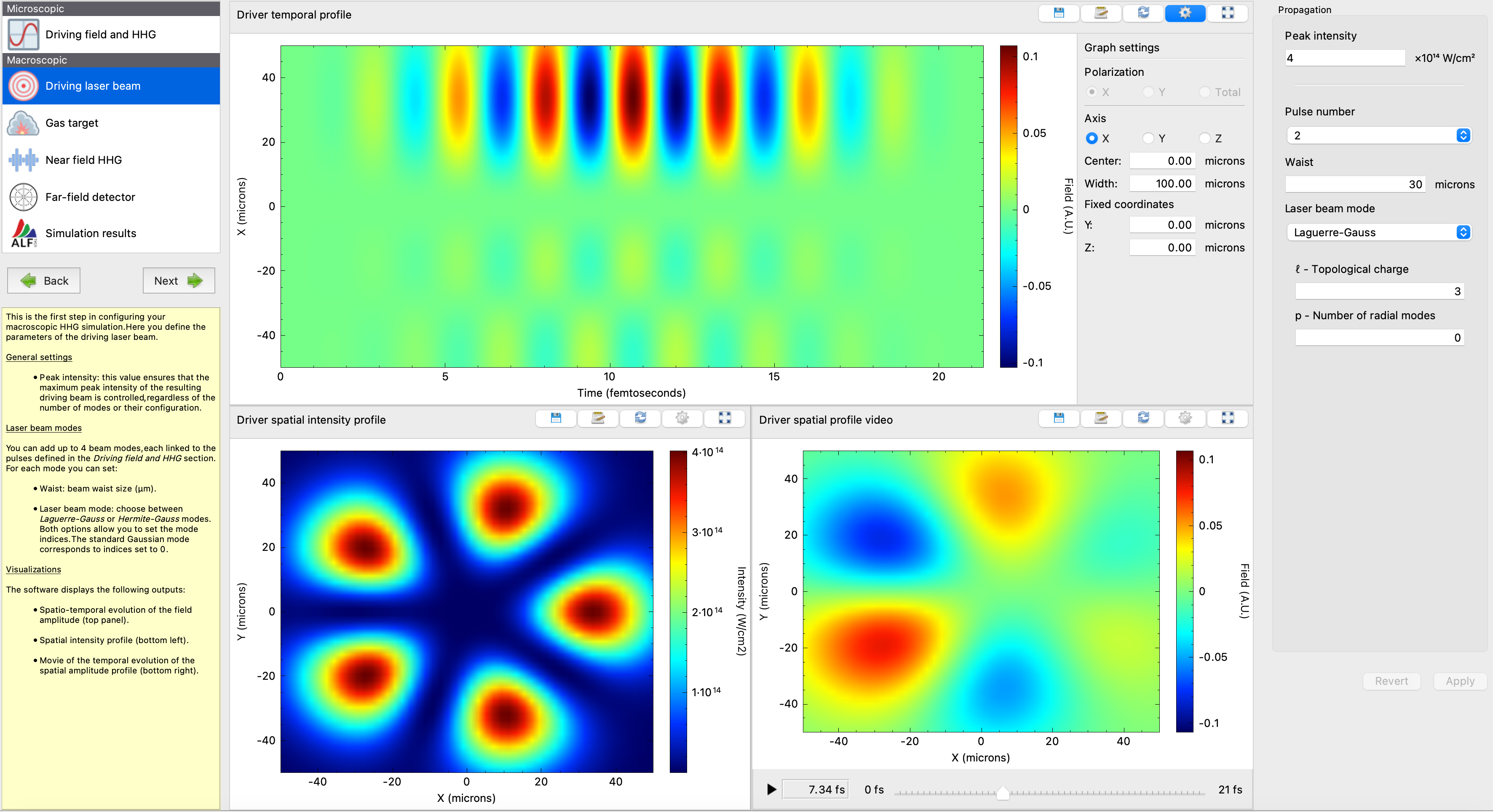

Configure the spatial profile

You can select the spatial profile using different Laguerre-Gauss and Hermite-Gauss combinations. You can visualize the field, intensity and phase of your driving pulse in the whole simulation space, with different graphical controls configurable graphs and a video control that shows the time evolution.

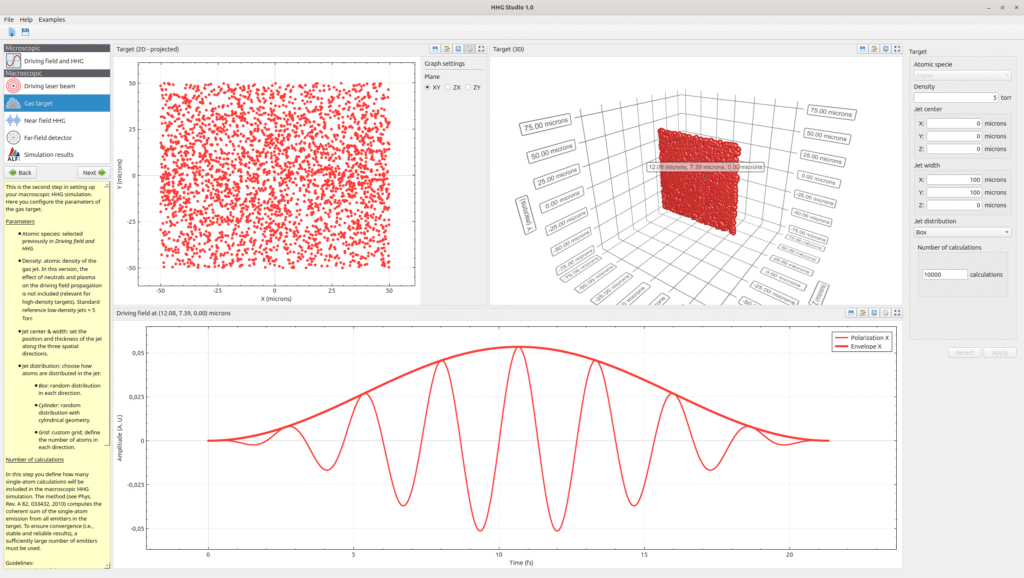

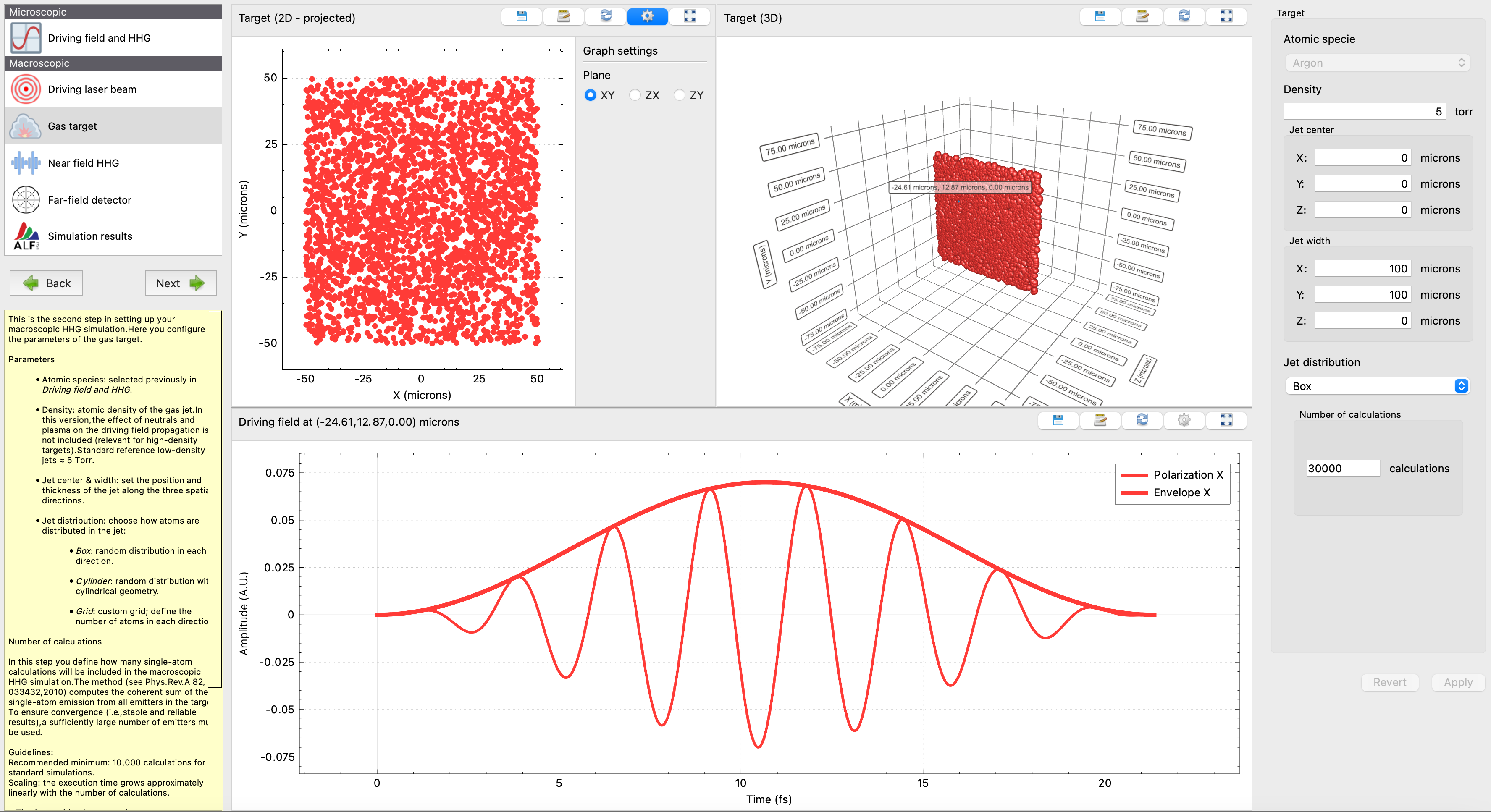

Set up your target

Select the location, shape and distribution and the gas of your target. You can configure a single plane or an entire volume for your macroscopic simulations. Selecting different points, you can preview your driving field.

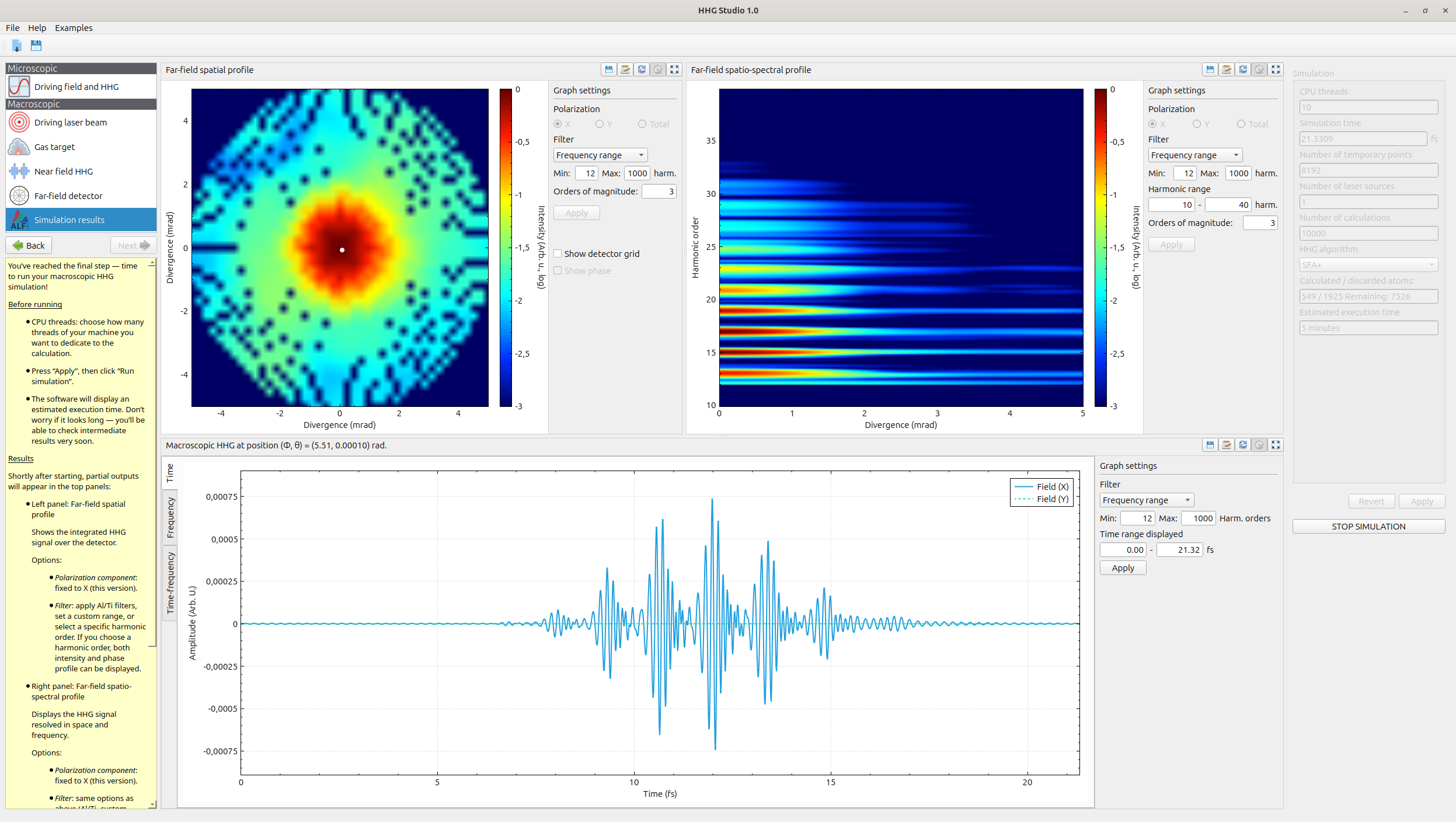

Analyze your results

Using the integrated graphical tools, you will be able to analyze your results, analyzing the emission at different divergences, focusing on a single point or using filters like Aluminium or Titanium. For a more detailed analysis using external tools, it’s also possible to export the raw data as text or as images.

Examples

Example 1: Selecting short trajectory contributions after propagation

This example shows how macroscopic propagation can suppress the long trajectory contributions and clean up the attosecond pulse.

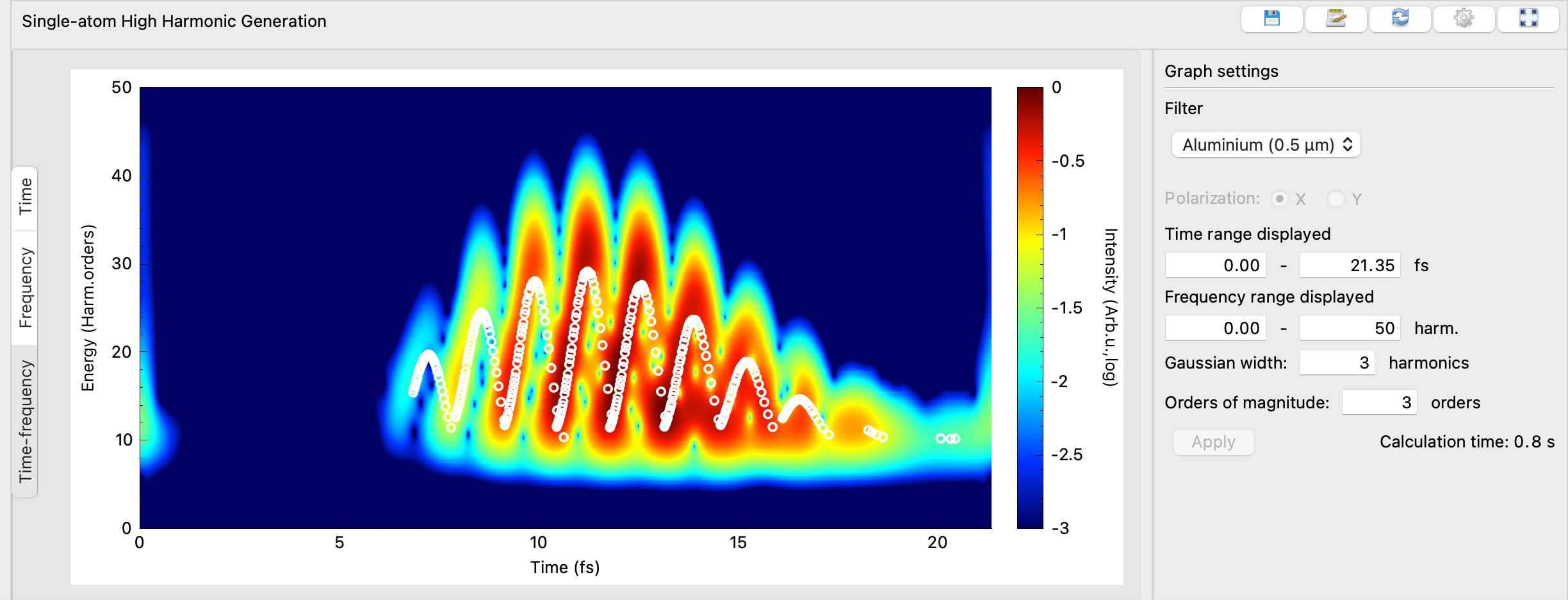

Step 1 – Driving field

Start with the predefined driving field parameters. To emulate an experiment, set a filter of 0.5 µm of Aluminum → this removes low-order harmonics.

- Check the resulting attosecond pulse → it looks quite messy because both short and long trajectory contributions coexist.

- The time-frequency analysis confirms this: the two contributions appear as structures with opposite slopes.

- Tip: the white dots represent the semiclassical predictions from Newton’s law.

Step 2 – Driving laser beam

Configure the beam with the predefined parameters. Use a standard Gaussian beam (Laguerre–Gauss with l=0, p=0) with waist = 30 µm. This represents a typical experimental driving field.

Step 3 – Gas target

Configure the gas jet as follows:

- Thickness: 100 µm in each cartesian direction.

- Distribution: homogeneous “box”.

- Jet center: positioned at the focus → Z = 0 µm.

- Increase the number of calculations (e.g., from 10,000 to 50,000) to ensure convergence in this test. (You can reduce it afterwards.)

Tip: by clicking on each atom position in the 3D view, you can inspect the driving field pulse at that location in the bottom panel.

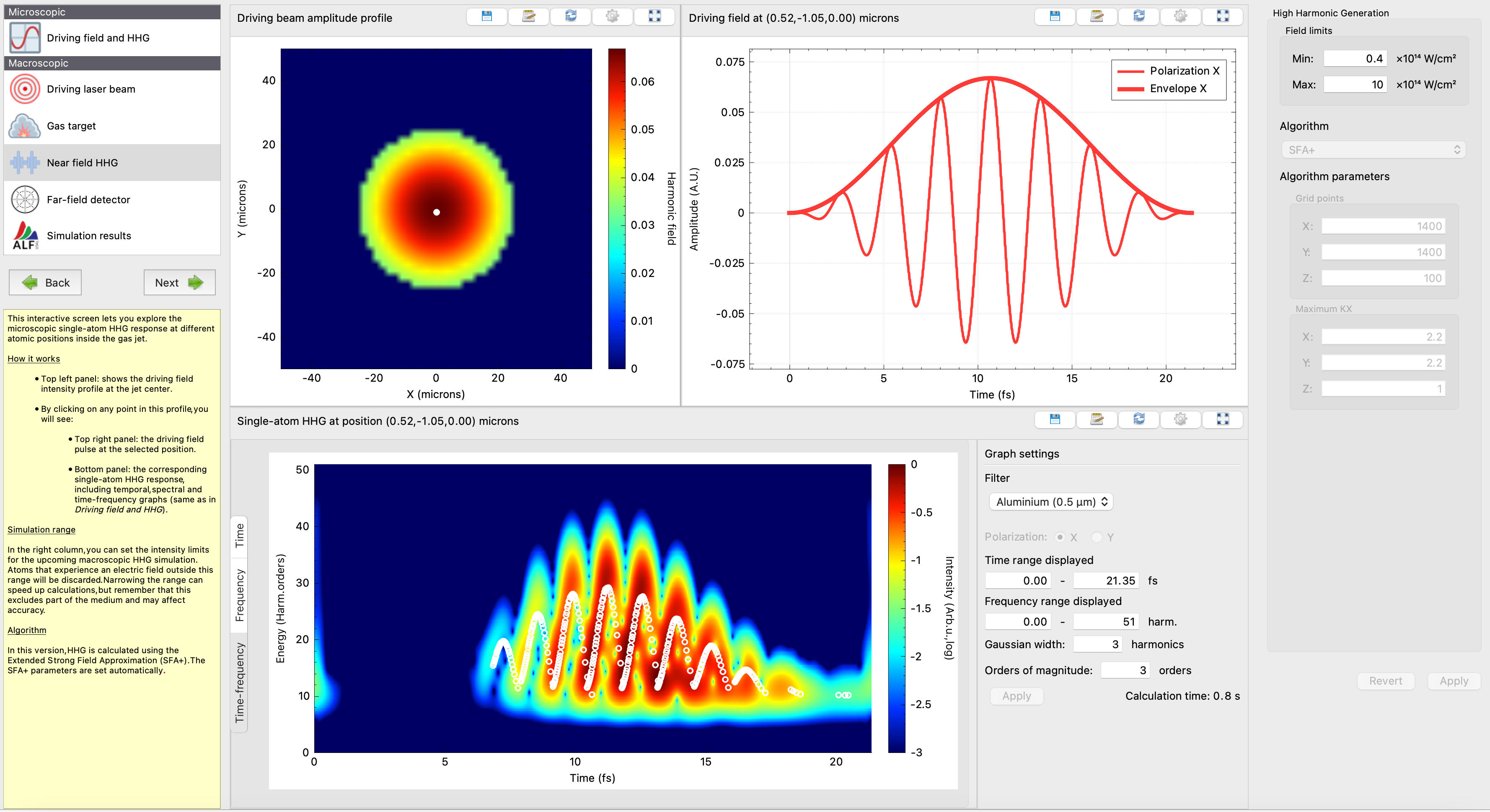

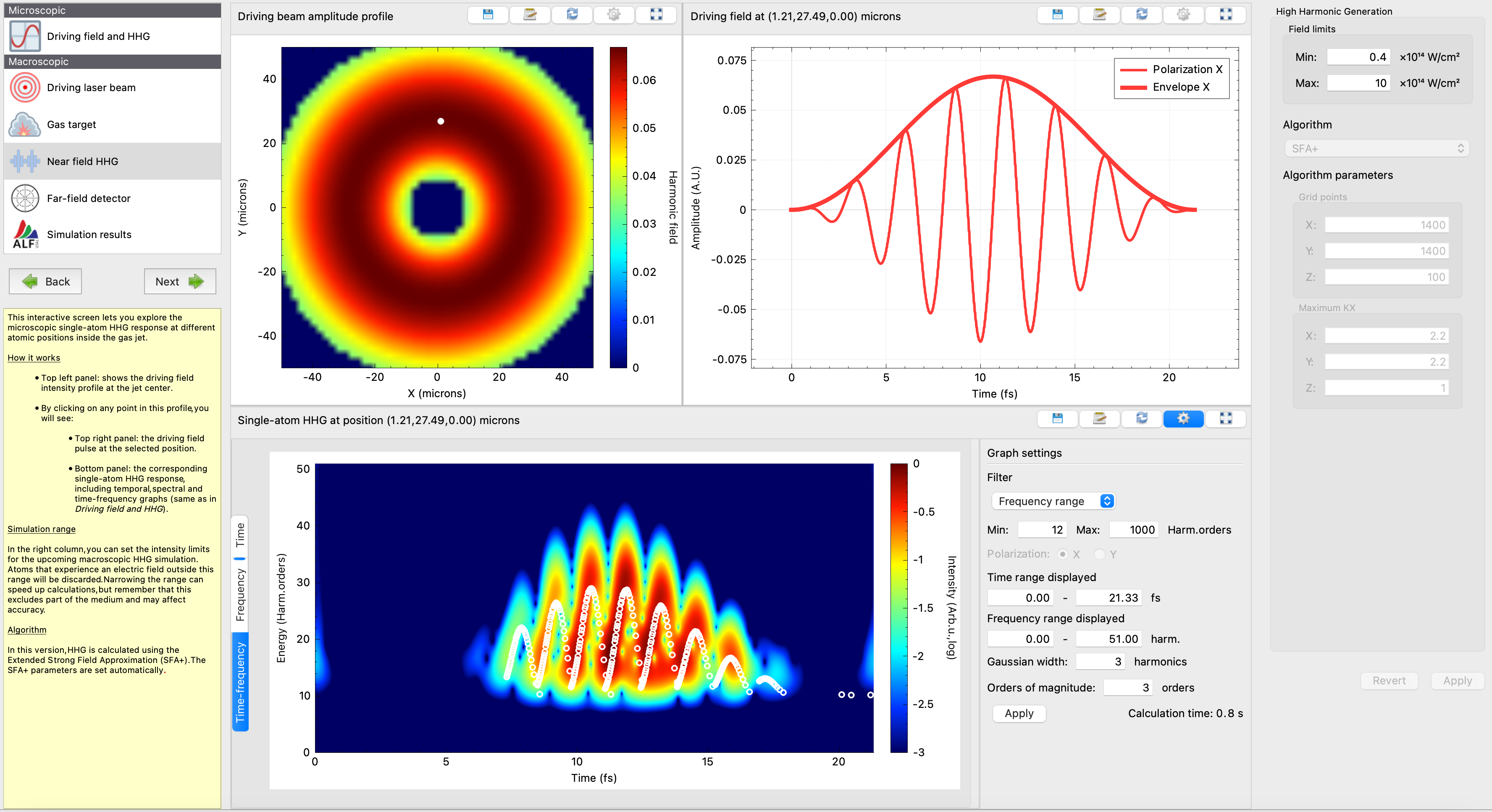

Step 4 – Near-field HHG

Inspect the single-atom HHG response at the center of the Gaussian beam.

- You’ll see both short and long trajectory contributions, similar to the purely microscopic calculation.

Step 5 – Far-field detector

Keep the default detector settings.

- If you modify the driving beam waist, remember to adjust the detector size accordingly.

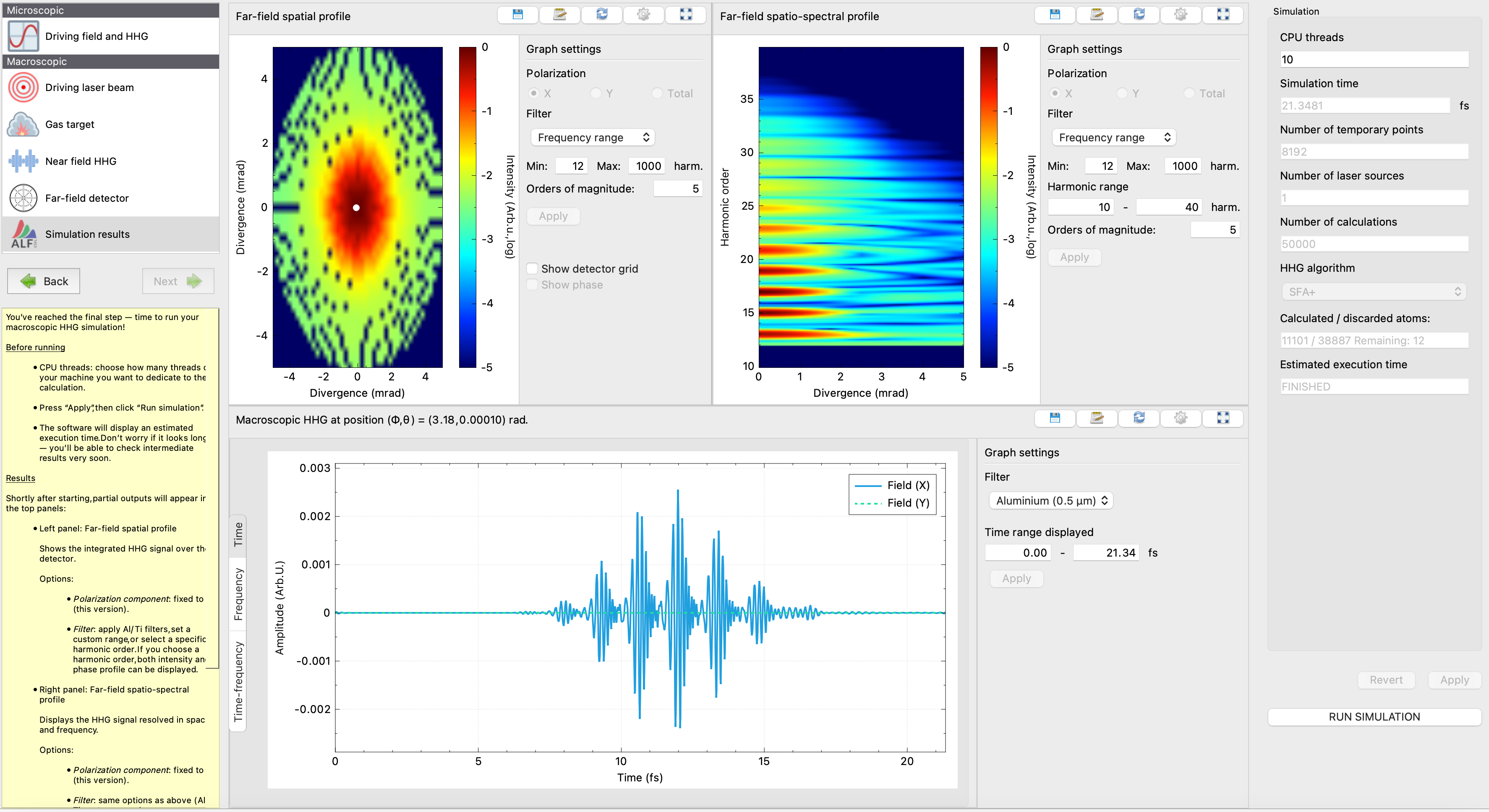

Step 6 – Run the simulation

Go to Simulation results:

- Using the increased calculation number (50,000), and depending on your computer, the complete simulation may take 10–30 minutes.

- You can already start exploring partial results while the simulation is still running.

Analyze the results

Focus on the center of the detector and examine the harmonic emission:

- The attosecond pulses are now much cleaner than in the single-atom case.

- The time-frequency analysis shows that the short trajectory contribution dominates after macroscopic propagation.

- This effect has been known in the HHG community since the 1990s (see for example Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3776 (1995), Phys. Rev. A 55, 3204 (1997)).

Example 2: Exploring the orbital angular momentum conservation law in HHG driven by a vortex beam

This example illustrates how the topological charge of high-order harmonics scales with that of an infrared driving vortex beam. This fundamental result was first predicted theoretically in Phys. Rev. Lett. 111 (8), 083602 (2013) and later confirmed experimentally in Phys. Rev. Lett. 113 (15), 153901 (2014); Nat. Commun. 7, 12583 (2016); ACS Photonics 9 (3), 944–951 (2022).

Step 1 – Driving field

Start with the predefined driving field parameters. To emulate an experiment, set a filter of 0.5 µm of Aluminum → this removes low-order harmonics.

Step 2 – Driving laser beam

Configure the driving vortex beam. Consider a Laguerre–Gauss beam with topological charge l = 1, p = 0, and waist = 40 µm. This represents a typical experimental driving field.

- Tip: In the driver spatial profile video, you can visualize how the spatial distribution of the real part of the electric field evolves during the laser pulse.

Step 3 – Gas target

Configure the gas jet as follows:

- Thickness: 100 µm in X and Y, and 0 µm in Z → approximates an infinitesimally thin layer, ideal to study transverse phase-matching effects in structured beams.

- Distribution: homogeneous “Box”.

- Jet center: positioned at the focus → Z = 0 µm.

- Increase the number of calculations (e.g., from 10,000 to 30,000) to ensure convergence for this test. (You can reduce it afterwards.)

Tip: By clicking on each atom position in the 3D view, you can inspect the driving field pulse at that location in the bottom panel.

Step 4 – Near-field HHG

Inspect the single-atom HHG response along the Laguerre–Gauss vortex beam.

- You’ll see how the local phase of the vortex beam affects the single-atom HHG emission.

Step 5 – Far-field detector

Keep the default detector settings, and:

- If you modify the driving beam waist, remember to adjust the detector size accordingly.

For this case of beam waist of 40 µm it is recommended that you increase the maximum divergence (theta_max) to at least 7 mrad. - For vortex beams, ensure good resolution in the azimuthal direction to capture the OAM structure.

Step 6 – Run the simulation

Go to Simulation results:

- Using the increased calculation number (30,000), the full simulation, and depending on your computer, the complete simulation may take 10–30 minutes.

- You can already start exploring partial results while the simulation is still running.

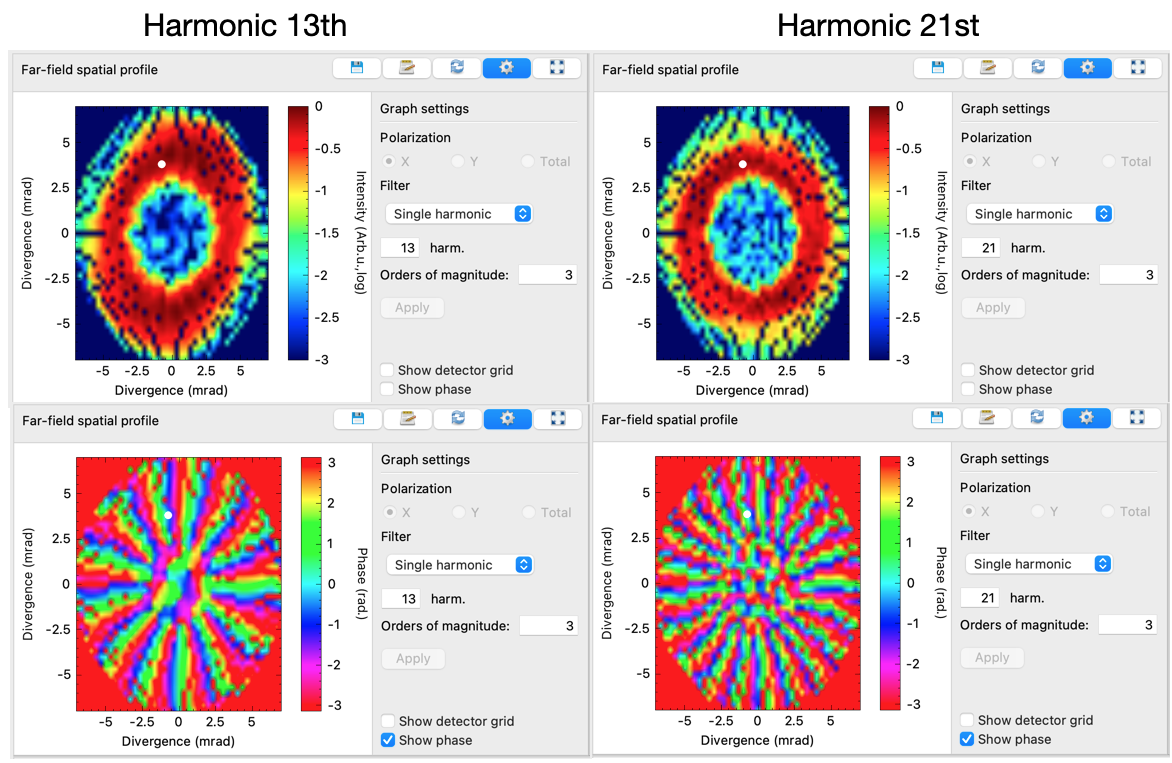

Analyze the results

Focus on the ring of maximum intensity at the detector and examine the harmonic emission.

- In the far-field spatio-spectral profile you can see that the divergence of each harmonic order is very similar.

- The spectral and temporal signatures (bottom panel) of the harmonic emission at different points along the ring are also similar. In this case we show the harmonic spectrum at a given point along the ring, in linear scale.

A particularly instructive step is to examine the spatial profile of each harmonic order:

- In the «Far-field spatial profile» view, select the filter «Single harmonic».

- View the intensity profile (default) and then switch to «Show phase».

- You will observe that the number of 2π phase shifts (topological charge) of each harmonic order scales linearly with that of the driving vortex beam.

Example 3: Generating high-order harmonic with a phased-necklace beam

This example shows how to generate high-order harmonics with a phased-necklace beam, as reported in Science Advances 8 (5), eabj7380 (2022). With this structured beam, it is possible to control both the harmonic line spacing and the divergence of the emission.

Step 1 – Driving field

- Use two laser pulses (use the control “Pulse number” to adjust the parameters of each pulse).

- To broaden the HHG spectrum, select Helium as the gas target.

- Increase the driving field intensity:

- For a desired final intensity = 4 × 1014 W/cm², and assuming both pulses are identical, set the intensity of each pulse = 1 × 1014 W/cm².

- Keep the remaining parameters: wavelength = 800 nm, 8 cycles.

Step 2 – Driving laser beam

Configure the phased-necklace driving beam.

- Set the desired maximum peak intensity (after coherent sum of the two modes) to 5 × 1014 W/cm².

- Define the two Laguerre–Gauss modes:

- Pulse 1: Topological charge l = +2, p = 0, waist = 30 µm.

- Pulse 2: Topological charge l = −3, p = 0, waist = 30 µm.

- Tip: In the driver spatial profile video (bottom right), you can visualize how the spatial distribution of the real part of the electric field evolves during the laser pulse.

Step 3 – Gas target

Configure the gas jet as follows:

- Thickness: 100 µm in X and Y, and 0 µm in Z → approximates an infinitesimally thin layer, ideal to study transverse phase-matching effects in structured beams.

- Distribution: homogeneous “Box”.

- Jet center: positioned at the focus → Z = 0 µm.

- Increase the number of calculations (e.g., from 10,000 to 50,000) to ensure convergence in this test. (You can reduce it afterwards.)

Tip: by clicking on each atom position in the 3D view, you can inspect the driving field pulse at that location in the bottom panel.

Step 4 – Near-field HHG

Inspect the single-atom HHG response along the phased-necklace.

- Set the field limit minimum to 5 × 1014 W/cm² to discard calculations whose HHG emission does not reach the higher-order harmonics. (We shall focus on harmonics above the 40th.)

- Observe how the local phase of each lobe influences the single-atom HHG emission.

Step 5 – Far-field detector

We focus on the central (on-axis) region of the far-field detector:

- Set the minimum divergence (

theta_min) to 0.005 mrad. - Set the maximum divergence (

theta_max) to 0.3 mrad.

Step 6 – Run the simulation

Go to Simulation results:

- Using the increased calculation number (50,000), and depending on your computer, the complete simulation may take 30–60 minutes. (This case is computationally heavier due to the complex phase-matching of the phased-necklace beam).

- You can already start exploring partial results while the simulation is still running.

Analyze the results

- Adjust the graphs to the spectral range of interest (40–80 harmonic orders).

- In the far-field spatial profile, select the on-axis position and examine the harmonic emission.

- Due to the selection rules in this case (Science Advances 8 (5), eabj7380 (2022)), the harmonic line spacing is fixed at 10 harmonic orders, so, starting from harmonic 40th, only 45, 55, 65 appear on-axis. The on-axis HHG spectrum is shown in linear scale, clearly revealing the three associated peaks.

- Inspect the intensity and phase profiles of the individual harmonic orders to study how the spatial structure of the phased-necklace beam shapes the HHG emission.

Download HHG Studio

HHG Studio is a software created by the Laser Application and Photonics Group of the University of Salamanca with the support of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 851201). It is compatible with Windows, macOS and Linux, and can be downloaded and used for free. Please send the form below and we will send the download link to your email: